After a few recent meetings and discussions, it has been an eye-opener for me to see that a lot of people seem to think they absolutely need to create or join a DLT consortium (distributed ledger technology).

Yes, on the one hand, blockchain and DLT are ‘consortium friendly’. DLT can ensure the usage of a common process while keeping confidential data private and secure thanks to elements such as zero knowledge proof. Data traceability can be ensured as can immutability of data and access and good order is promoted because everyone follows the rules of the network by using smart contracts.

A DLT consortium has natural advantages too. It leverages the complementary strengths of the different participating businesses, bringing the opportunity to quickly and cost-effectively establish highly-differentiated positions within a marketplace. A consortium also allows companies to leverage the benefits of DLT for their own specific needs and streamline (common or joined) business processes of common concern to all consortium members.

However, it can also be a minefield. There has been no shortage of consortia being formed but skeptics would say there has been a dearth of positive outcomes. When Facebook announced, with great fanfare, in June 2019 a consortium called The Libra Association to develop a “global currency and financial infrastructure”, it looked to be a potential game changer. However, it ran into trouble when seven key members – Booking Holdings, eBay, Mastercard, Mercado Pago, PayPal, Stripe, and Visa Inc. – decided to leave the initiative even before its first meeting in October.

Do you really want a consortium?

There is nothing wrong with the aspiration towards a consortium, but it can often be ‘putting the cart before the horse’. A consortium needs to be based on an agreement to do something specific, as that is what brings you an advantage but is often missing. The core business objective (and the agreement on what data serves that objective) needs a lot more thought before trying to create a consortium, which comes with many complex legal and psychological barriers.

Let’s remind ourselves of why the blockchain excitement kicked off in the first place. Stripped back to its essentials, DLT is a data technology that enables information sharing with high transparency and reliability. However, it cannot be stressed enough that it is not just about sharing data but about shared control over data.

The data in the chain and the means of controlling it should therefore be the basis of any agreement before a consortium can come into being. For example, a raw plastics manufacturer is increasingly concerned about where its products end up – in rivers, the sea – and the damage to the environment and its reputation. It starts to talk with its downstream partners – a global chemical company using its products for plastic bottle packaging and the retailers who sell those products – about a DLT-based plastics tracing platform. Do they need a consortium to do that? No. An agreement to share data is all that is needed in the first instance.

That may lead to other things but, by that point, the shared understanding about how to use the data and the trust between the parties is in place to build a bigger, more ambitious undertaking. This is an equally valid way to start building an end-to-end supply chain consortium. It is vital that any agreement can stick, but the business problem comes first – don’t get hung up on a consortium without a prior agreement on the underlying data.

Why consortia fail

This lack of a firm foundation explains why so many DLT PoCs don’t make it to scale. They don’t have a clear understanding of a purpose that meets the needs of an ecosystem and an agreement in place about the data in that ecosystem. In fact, 90% of consortia fail – generally for 3 reasons:

- The first is a lack of involvement and a failure to achieve the defined goal. If participants don’t see any progress, the group is not active enough or the participants can’t find common ground, then members start to wonder if the consortium is a smart allocation of their resources. Therefore, it’s easy for an imbalance in contributions to develop. If one company doesn’t feel like the others are involved, it may well decide to pull out, creating a domino effect.

- Second, the consortium may have the wrong funding and economic model. Creating a DLT consortium is expensive because gathering the right people with the right skills is costly and it only delivers value over the long run. Therefore, without a sustainable economic model, the consortium cannot last a long time enough to realize its objectives.

- The third cause of failure is governance. The assignment of authority and responsibility among the consortium members determines who can read/write data, contribute in the consensus mechanism, participate in decisions, update the system and allow new actors to join the network. This distribution of power between a group of competitors has an impact on the business model of the use case and the involvement of the participants.

Governance models

In any consortium, there is either one dominant party, who calls the shots or, more usually, a range of parties, each with roughly equal heft. This may include regulators, and each imagines they can dominate. In either scenario, there is simply too much potential for misunderstandings and sheer corporate or personal ego to get in the way of success.

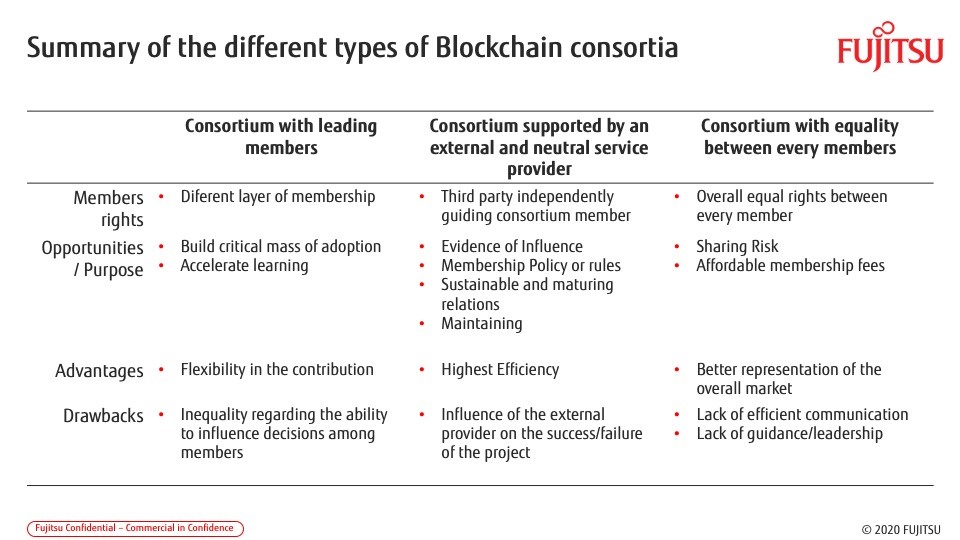

However, there is another way – a consortium supported by an external and neutral service provider (see diagram for a summary of the governance options). Here a neutral third party holds the ring, either directly or on behalf of another dominant party, creating a more hybrid model. It must have the technical knowledge to mediate and make the consortium work.

Making things simple(r) – Blockchain-as-a-Service

One easy call you can make to simplify consortium management is to take advantage of Blockchain-as-a-Service, where a service provider develops and maintains a DLT solution in the cloud on behalf of the consortium. This can bring many advantages at a faster pace. It provides immediate and reliable access to technical and non-technical DLT specialists, ensuring the performance of the infrastructure. Externalized development, deployment, and maintenance of the solution allow the consortium to focus on the core business issues. And it is simply more cost-effective, especially where capital expenditure is concerned – likely to be one of the main constraints for any new undertaking.

Questions to ask yourself before starting a consortium

To help potential consortia members decide whether they have the basis for a flourishing ecosystem, Fujitsu has developed two sets of questions that can considerably accelerate time to value – and avoid costly mistakes in the first place.

The first is the seven signs that indicate where further investigation is warranted. If it is, the second model contains another set of seven questions about consortium purpose and structure where solid answers are mandatory to achieve real and sustainable value over the long run.